How (most) reflections in games work

How (Most) Reflections In Games Work

In nature, lighting tends to function a lot easier than in rendering. Light rays are emitted from light sources, and reflected from surfaces. If they end up in a camera or eye, we see the color of the light/the reflected surface. The problem: Simulating millions of rays of light is expensive. That’s why most real-time renderers don’t bother simulating those rays (this actually starts to change somehow - but very slowly). Instead, they use an algorithm called rasterization. Explaining it might be out of the scope of the article, but to summarize it, most renderers assume that if a surface is in front of a camera, the camera will record the color of the surface at this point - without checking where a potential light ray between this surface and the camera might be blocked or sidetracked. This is a problem. To simulate reflections we need to simulate light rays bouncing of shiny surfaces.

Introducing Reflection Probes

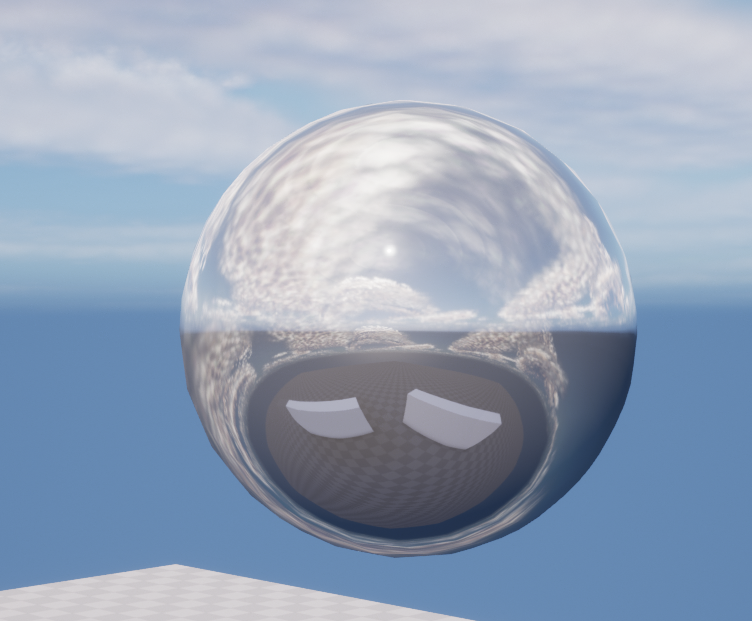

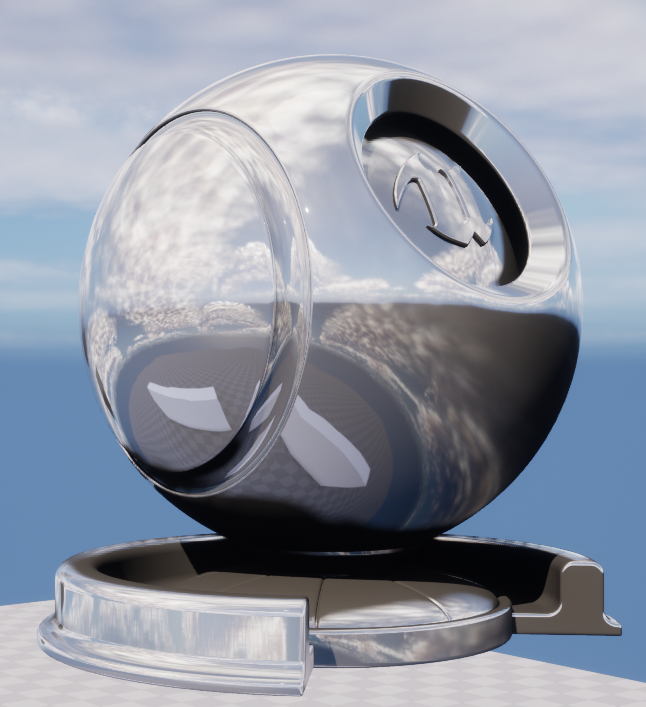

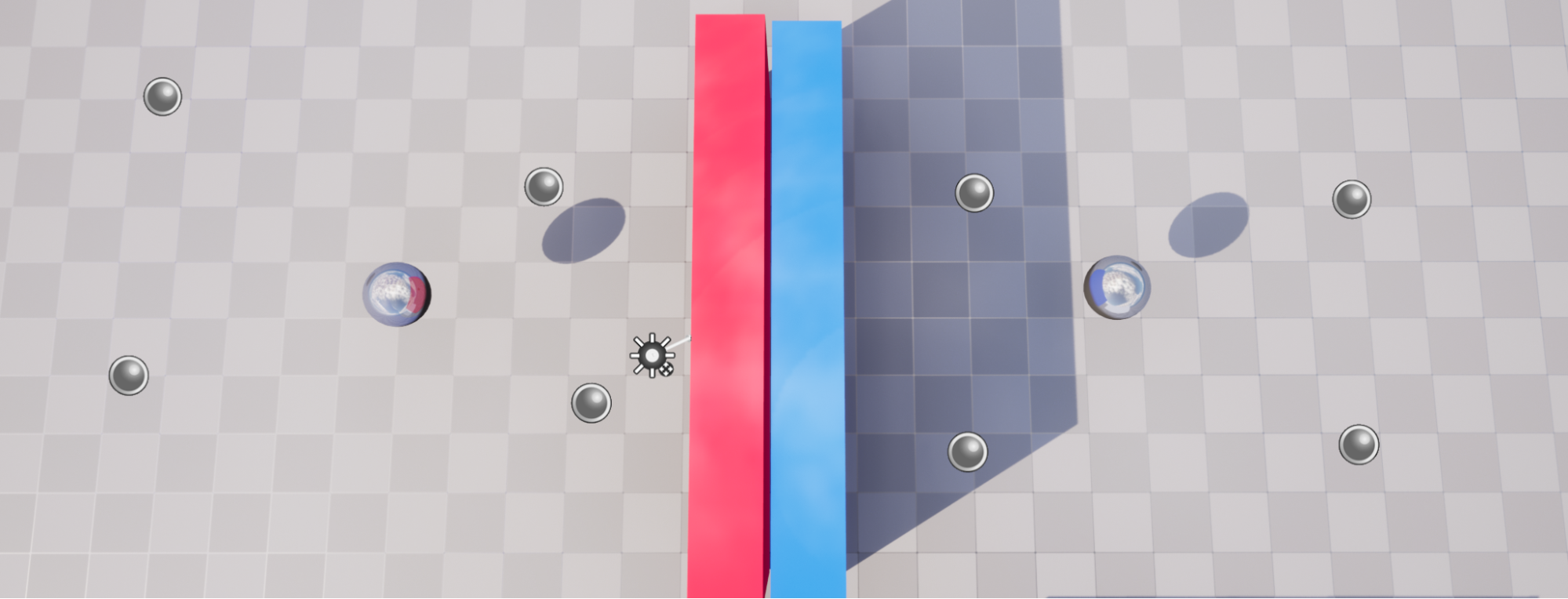

One common solution is the use of Reflection Probes (called Reflection Capture Components in Unreal). Let’s start with a simple example: A sphere.

We can’t simulate reflections, but we can render the scene from the viewpoint of the sphere, as a 360° image and use this as the texture of the sphere, which mimics a perfect reflection very well. This 360° is also called a cubemap giving this technique its name: Cubemap reflections.

Sidenote: In general this technique is called Reflection mapping with cubemaps being just one of possible projection methods for such a 360° texture. But the name Cubemap reflections is much more common, even if it is not always 100% correct.

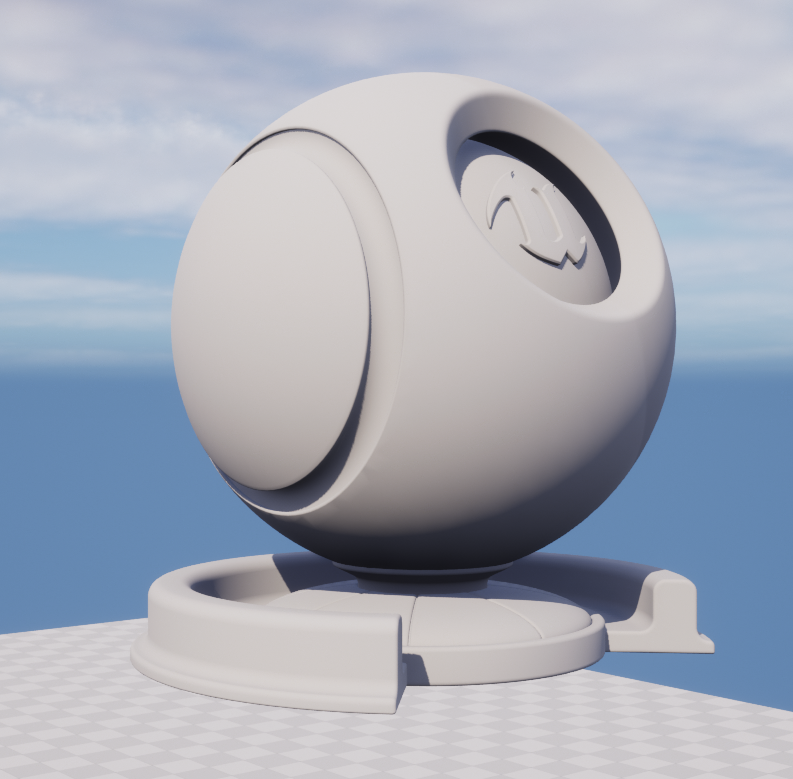

All of this is straightforward on a sphere, but what about a more irregular shape?

We can’t use this trick now, right? Well, we can try. Let’s just use the 360° texture from the sphere, and try to match it to this shape. To do this we assume that every point of the mesh will reflect the same pixel as the sphere if its normal points into the same direction.

This looks… surprisingly convincing. On close inspection, we notice that this reflection isn’t correct. There are some ugly stretched areas in places where the surface normal doesn’t change and some areas reflect points of the scene that shouldn’t be visible to them. But with the exception of plane mirrors most reflective surfaces warp the reflection anyway and since this technique is extremely easy to calculate, we can live with those drawbacks.

Extremely easy to calculate is no exaggeration: even in the early 2000s, consoles were fast enough to display reflections in this way. Here is a slightly later, but very nice example from Flatout 2. Not only are there large scale reflections of the environment in the windows of the skyscrapers, the car seems to reflect nearby buildings and the sky.

But especially in those early games it’s easy to catch all the drawbacks that come with this technique. First of all, up to this point we did just render one cubemap. A single map can only represent reflections for one point of the level. As soon as the reflective surface starts to move away from the point of capture (which moving surfaces like cars tend to do), the reflection becomes incorrect. Dependent on the level, this might be more or less noticeable. Take a look at this screenshot from the same race, just seconds later.

In this scene the same car is driving through a shopping mall - but the car roof is still reflecting the blue sky from before. For the reflection on a fast moving sports car it might still be good enough as long as there is something being reflected. After all, on an irregular shape as a car we can’t recognize too much of it anyway. But in case of large, contiguous surfaces, this illusion breaks rather quickly if the cubemap doesn’t match the environment.

Or even worse, sometimes the cube map doesn’t even show the level at all:

https://twitter.com/dark1x/status/1685166191407513600

Luckily there is an easy solution, we just need to use multiple cube maps for different points of the level. To do this we just mark all points where a reflection should be captured with a reflection probe. When an object moves around, we just blend between the nearest reflection maps and - tada - fitting reflections for every point of the level.

Working with reflection probes

But wait - now we have two new problems. For once, we need to place potentially a lot of those reflection probes. Dependent on the size and complexity of the level hundreds or even thousands of them. A task that many studios tend to automate, but of course writing such an automation also takes time.

The second problem: Hundreds of reflection probes will produce hundreds of reflection maps, all of them occupying precious memory on the GPU. For this reason, most games use rather small reflection captures, the default size in Unreal is just 128x128px. This size can be increased in the project settings, but obviously, this should be avoided if possible.

You may have winced at the mention of this size. 128x128px? Shouldn’t reflections be super blurry then? The answer is, yes actually they tend to be quite blurry. We will come back to this problem later.

But there is another, third problem, that I avoided to mention until now. So far we assumed that the reflection map is rendered just once, before the game is even started and can be reused every frame. This is true - as long as nothing moves inside the level. Sadly, most games contain moving objects (citation needed) which won’t show up in our pretty reflection maps.

Because of this most games do not rely on reflection probes alone to render their reflections. Instead they will mix it with other types of reflections. The most commonly used type for this is probably the use of Screen Space Reflections (SSR).

Adding Screen Space Reflections

We need another type of reflections that is updated in realtime so it can capture moving objects as well. If possible even in a less blurry way.

The main obstacle to this is the realtime update requirement. Rendering a whole reflection every frame is definitely too slow, so Screen Space Reflections use a clever trick to avoid it.

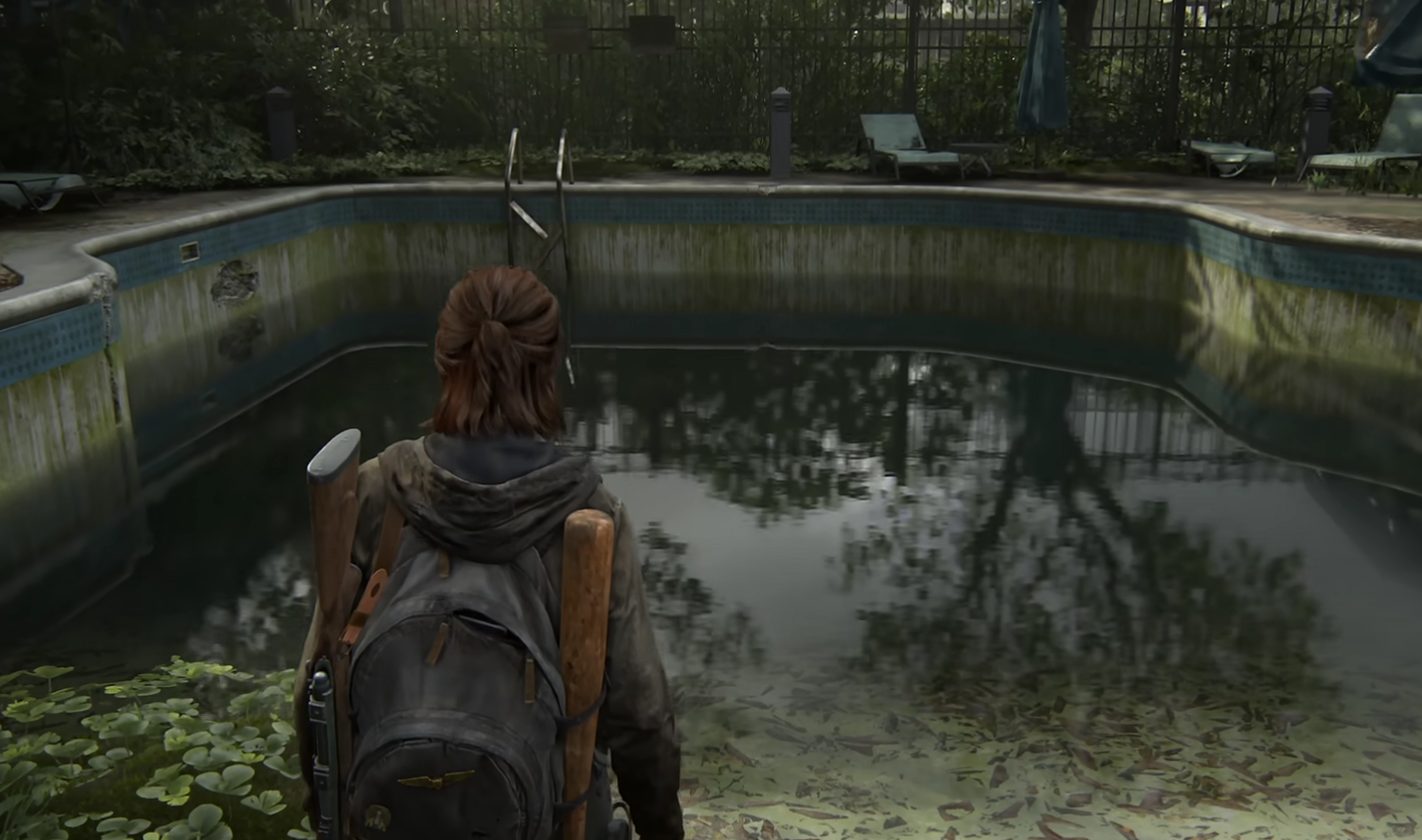

When looking at reflections you may notice that often the content of the reflection was already rendered elsewhere in the frame. In this example from Uncharted 4, the legs of this guard are visible twice. Once in the reflection in the puddle and only a few pixels above.

Wouldn’t it be a waste to render the same pair of legs twice, just to show them in the reflection? Wouldn’t it be enough to render them once and just copy and flip the result? Well, this is exactly how Screen Space Reflections work. First, the whole frame is rendered, without any reflection. Afterward, parts of the rendered frame are copied, flipped, and blended into the reflective parts of the frame.

This mirroring is done only in 2d space, based on the direction the normal is facing. If it is pointing up the pixels are copied from the space above the surface, if they would point downwards, like it would be the case with a reflective ceiling, pixels from below the surface would be used.

Since no “new” pixels need to be rendered this process is extremely fast, and can be done every frame, while also showing dynamic objects like this guard. At the same time, Screen Space Reflections can be done at full resolution, avoiding the blurry results of reflection maps.

So far the the technique seems like a magic bullet: It’s sharper, can reflect even moving objects, and is super cheap. Is there anything it can’t do?

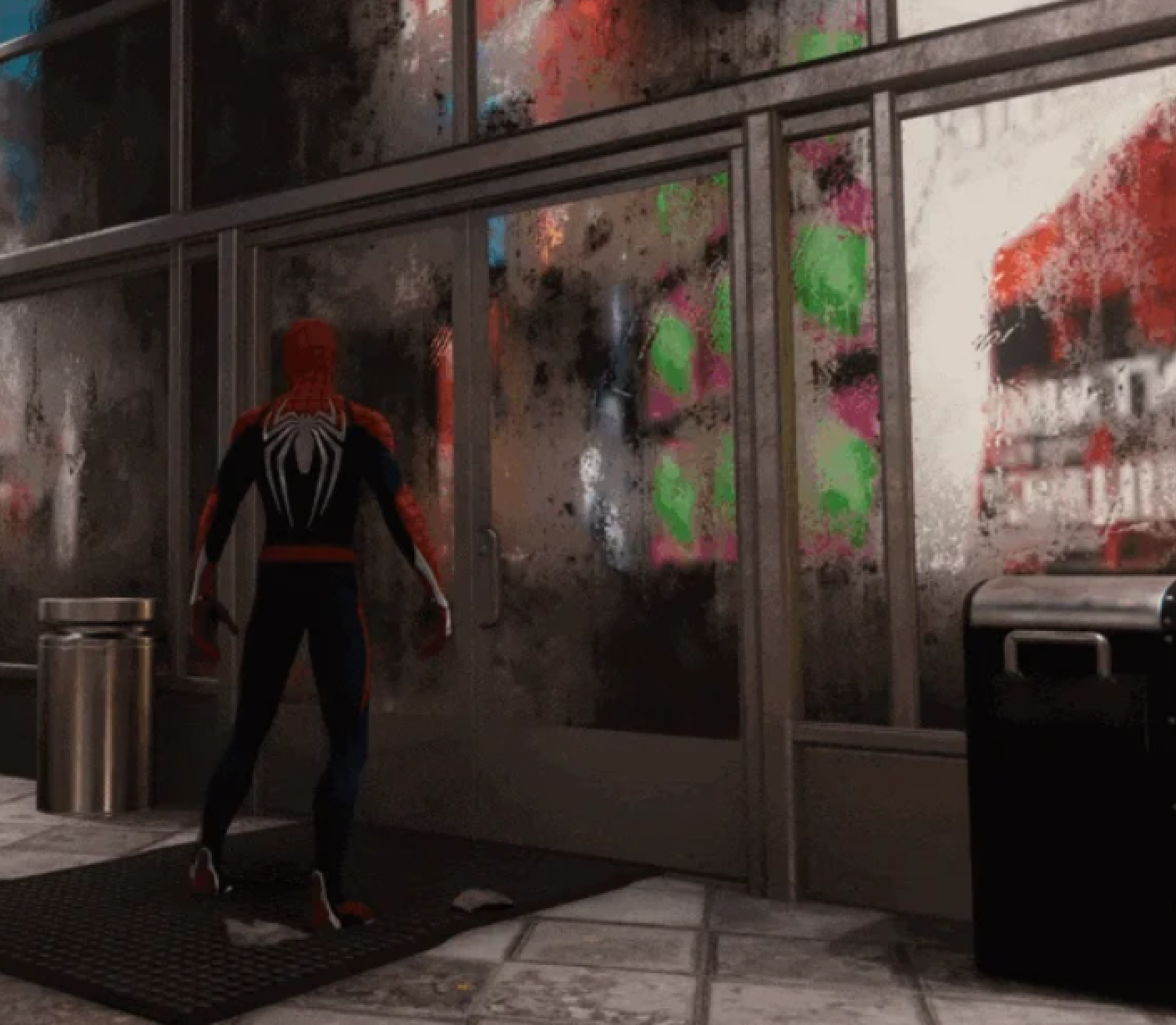

As explained and already apparent from the name of the technique it only works in screen space, meaning that objects that are outside of the screen can’t appear in the reflection - we can only reuse pixels that are already rendered.

So what happens if things move offscreen? In the most simple case, the reflection will just disappear. In reality, most engines will fall back to the nearest reflection capture or - if none can be found - at least blend out the reflection smoothly so the lack of a proper reflection isn’t that noticeable. If you want to delve deeper into this topic I strongly suggest the Dev Blog of Brickadia that describes how you can further fudge Screen Space Reflections to hide it’s shortcomings: https://brickadia.com/blog/devlog-5/#improved-screen-space-reflections

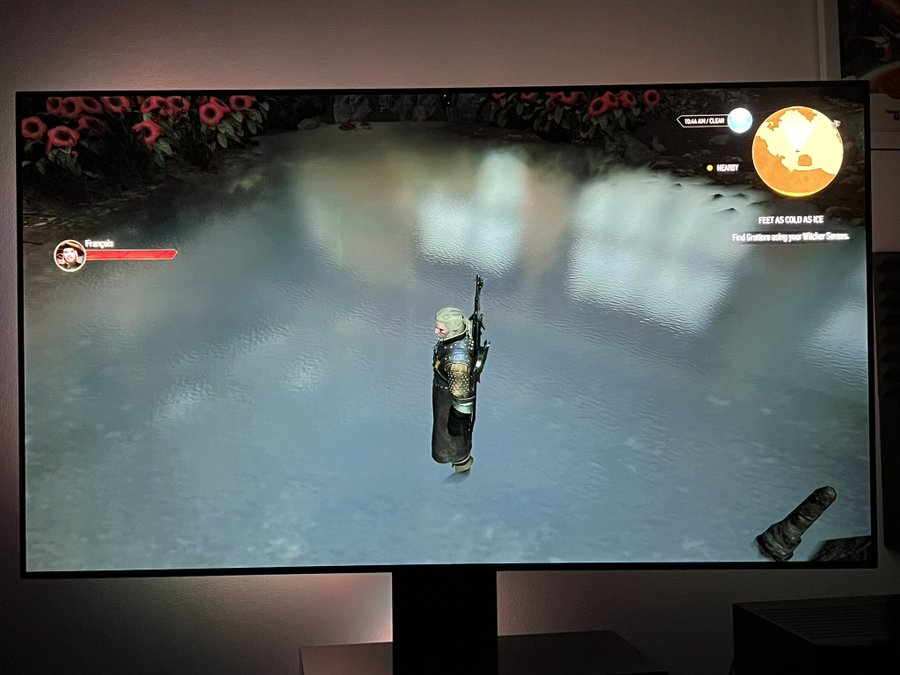

One quirk of the Unreal Engine is, that Screen Space Reflections don’t check if the reflected area is actually behind the reflective area. Take a look at this palmtree. It’s miles away from the ocean in the background, in theory it should not be possible for the tree to appear in this reflection.

Perspective Issues

Another drawback: The reflections are done in 2d space, meaning they are rendered from the viewpoint of the camera, not from the viewpoint of the reflective surface. Especially if the reflective surface is almost orthogonal, this causes big differences in perspective. There is not a lot we can do to fix this, except changing the scene layout manually to avoid this issue, which in most cases is probably not a worthwhile time investment.

Should I use screenspace and cubemap reflections?

Nowadays there are multiple alternatives to those ‘old school’ reflection types. Mainly raytraced reflections that are starting to become common in almost any major engine out there and - if you develop with Unreal - Lumen. Both avoid many of the described shortcomings by offering higher resolution reflections with less perspective issues without the need of pre-baking any data. The drawback: They both require a lot of hardware power, that not all platforms can bring to the table. Even though most consoles out there (not you, switch) support raytracing in theory, but due to the high impact on framerate only as an option.

For the foreseeable future, both of these reflection types should be set up to work in your game, even if they just serve as fallbacks to nice, modern raytracing.